1) Einleitung

This blogpost will explain my workflow for shooting deepsky objects and collecting data (“light frames”) during an astrophotography session.

If you’re interested;

- the ersten Beitrag dieser Serie explains the “drei Bedingungen für die Astrofotografie“

- the second post of this series covers everything around planning an astrophotography session

Alle Blogeinträge der Serie "Vom Plan zur Bearbeitung" gibt es hier.

Nebenbei bemerkt: Ich bin Hobby-/Amateur-Astrofotograf. Meine Absicht ist es, die grundlegenden Aspekte der Astrofotografie zu beleuchten und sie Anfängern zu erklären. Mit anderen Worten: Es ist mein Hobby, und ich pflege diese Website in meiner Freizeit. Bitte also um Verständnis dafür, wenn einige Inhalte veraltet sind. Zum Zeitpunkt des Schreibens zeige ich, was ich tue, um Ergebnisse zu erzielen, mit denen ich zufrieden bin. Diese Blogeinträge sind auf Englisch geschrieben und werden automatisch ins Deutsche übersetzt mit DeepL.

2) A brief overview of the different frame types

Before I start explaining my astrophotography session in Sequence Generator Pro, let me briefly explain the different frame types you’ll come across. I’ll divide them in two categories, so it’s easier to understand.

2.1) Frames, that contain deepsky object information (the “real” image)

How many light frames you shoot depends on the “drei Bedingungen für die Astrofotografie“. As a tip: have a look into Astrobin and search/filter for your deepsky object and how others collected data.

- a “light frame” is basically an image that contains all the information you want to have in your final picture – a nebula, a galaxy, a comet, …

That’s all :)!

2.2) Frames, that are used for calibrating your light frames;

In general, I take 50 of each of the following frames and stack them into so called “Masters“. Those calibration frames allow you to (mathematically) remove a variety of confounding factors from your light frames.

- a “flat frame” (Master Flat) contains vignetting and all the “bad” things (e.g. dust particles) that block/disturb your light train.

- a “darkflat frame” (Master DarkFlat) is used to calibrate the flat frames.

- a “dark frame” (Master Dark) contains the dark signal and the so called “thermal noise” if your sensor is not properly cooled. Besides that, they’ll also allow you to tackle hot and cold pixels.

There are also so called “BIAS frames“, but I’m not covering them here.

2.3) When to take calibration frames

As a summary, I’d like to highlight the following;

- flat frames und darkflat frames should be taken for each session (where a session is kein only limited to one night!). There is no general rule that applies.

- a set of dark frames can be taken once per exposure time (e.g. 180sec, 300sec, 600sec) and then serve as a library for multiple future sessions.

There are a lot of great tutorials available – so if you’re interested make sure to check them out!

3) Session preparation with Sequence Generator Pro (SGP)

At this point I assume that you’re familiar with deepsky object target selection and know how to plan your astrophotography sessions properly. At the time of writing this blogpost, I’m collecting data (light frames) for multiple objects;

The reasons for shooting multiple deepsky objects in one night are;

- optimizing the output of a clear night based on the “drei Bedingungen für die Astrofotografie“

- making use of altitude charts that I’ve described in the second post of this series

Remember, we’re looking for quality, not quantity. So I always aim for (less) light frames in the best possible quality, rather than a vast amount of data which is not usable.

4) Live Session Example – IC1396 and M51

4.1) IC1396 – “Elephants Trunk Nebula”

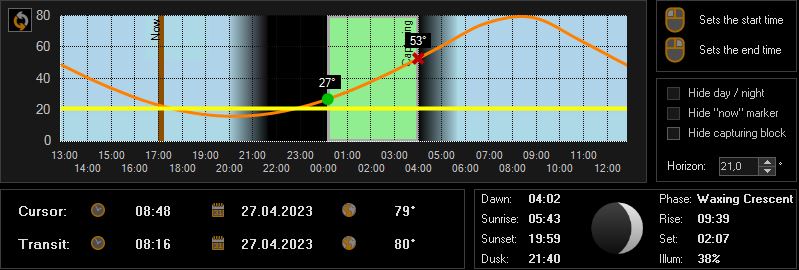

I’m favoring IC1396 based on its rise over 27° above horizon – so that deepsky object is our starting point. For more details on that threshold please see the ersten Beitrag dieser Serie.

As you can see in [Image 1] I defined the start time as soon as IC1396 rises above 27° over the horizon, which would be roughly at 00:10 in the morning. The end time has been set to 04:00 as SGP tells us that dawn begins at 04:02 (for more details on twilight please check out the section in the second post of this series).

4.2) M51 – “Whirlpool Galaxy”

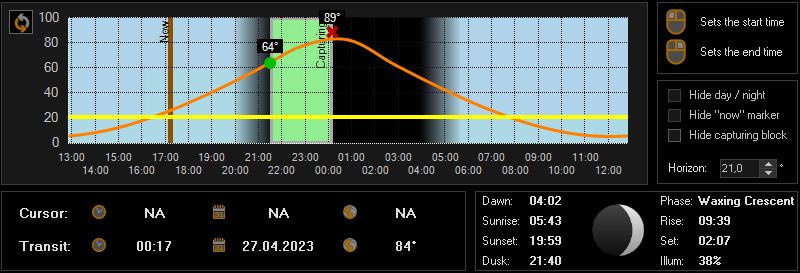

That leaves us with an “empty timeframe” between 21:40 (=dusk) und 00:10 (=when then integration of IC1396 starts). To find proper targets, I had a look into Telescopius and chose M51, because I need RGB light frames of IC1396 anyhow. A perfect match so to say :)!

Explanation: I don’t have an electronic filter wheel (yet) that would change filters (RGB<->dual-narrowband) automatically based on the configuration in SGP. So if I needed to shoot M51 with RGB and IC1396 with my dual-narrowband filter in the same night, I would need to set an alarm to midnight and manually change the filters. An electronic filter wheel takes care of that for you. So, as part of my session planning, I always shoot multiple objects with the same filter per night.

[Image 2] shows that it would be possible to shoot M51 throughout the whole night, but I also want to finish collecting data for IC1396. So I’ve configured SGP to start taking light frames at 21:30, 10 minutes before dusk.

Explanation: I always set “dusk minus 10mins“, because SGP needs to center on target and run auto-focus before starting “integration”. As stated earlier I really want to use the integration timeframe to the best possible extent.

4) Preparing the observatory

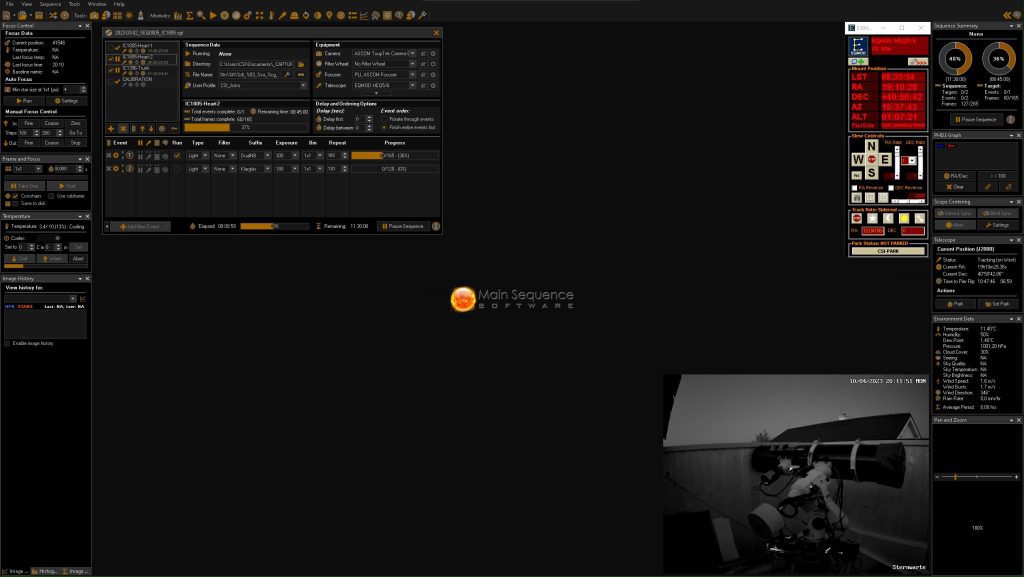

I want to really keep this section short, because it varies from observatory to observatory and site to site. In my case, I can simply “roll off” the roof of my observatory and that’s it. Afterwards I’m powering up my mount, my astrophotography cameras (main and guiding) and my auto-focuser. Once you have configured your “equipment profile” in SGP, it allows you to connect to all devices at once.

I usually do this minimum 30 to 60 minutes before the integration starts to allow my equipment to cool down and acclimate.

[Image 3] shows SGP waiting for the integration start and already connected to all mydevices. The astrophotography camera is automatically cooling down to -10°C on connect and the mount is unparked via EQMOD. Also PHD2 is waiting for the command to start guiding. In the lower right corner you see a livestream of my surveillance camera that I’ve installed to check if everything is fine.

5) What a raw light frame looks like

The following [Image 4] is an un-processed RAW image displayed in SGP. It was “stretched” (the process of making faint information visible – to keep it very simple) to see what’s in the image.

As you can see it’s in B/W, because it has not been de-bayered yet (I’ve described the Bayer-matrix briefly in the ersten Beitrag dieser Serie).

Abschließende Worte

In this blogpost we had a first look in how to shoot deepsky objects.

- I’ve described the different types of frames in astrophotography

- I showed you how I planned my astrophotography session for both IC1396 and M51 in one night

- I listed what I do to prepare my observatory

- Finally, I showed you a raw light frame without any further processing

In the next post of this series, I will show you some basic pre-processing steps. CS!